Pop Art, I imagine, was the mother of all explosions of colour upon a dreary post-war landscape. Work began to emerge that placed advertising, consumerism and celebrity centre stage. Andy Warhol painted soup cans and screen-printed Marilyn Monroe’s face. Richard Hamilton collaged together all the elements that represented ‘New Britain’: the taglines of advertising that would entice us into buying a Hoover, as the idyllic aproned woman cleaned, the ideal man flexed his muscles in the foreground and a tasty ham perched on a table nearby. Robert Rauschenberg, Peter Blake and countless others made their mark with work that both celebrated and satirised these new hallmarks of society.

This is what Pop Art will forever represent; this knowledge will forever be regurgitated. Yet, the new show at Saatchi allows us to see beyond this, to the ongoing impact that Pop Art has had. Specifically, we can see the impact not only on art being made now, but also upon the work that was being made in Russia and in China, in societies where Communist propaganda was the main source of visual imagery and capitalist values were stigmatised.

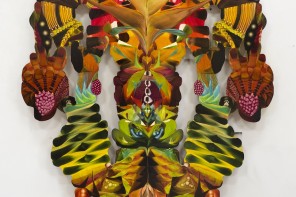

But first, let me lead you through the first couple of rooms and the work shown under the umbrella heading of ‘Habitat’. That riot of colour that, for me, was one of the defining features of Pop Art, seemed to be non-existent, at least in the first room. It was curiously muted, almost as though saturation point had already been reached. The love affair with commodity that Pop Art had exemplified had been stripped down to neutral colours and oversized objects; it had been rendered as something big and ridiculous, as well as bare. For me, it seemed to mock the present day’s obsession with consumer goods as something inflationary and overvalued. There was an overblown sink (with wings) on the wall, and a marble armchair in which Ai Wei Wei had crafted the most exquisite creases. There was a mattress, toilet rolls cast in plaster and an unfinished installation from Ilya Kobakov: paint cans and pieces of wood, with plans lying around. It was almost as though the promise of what something could be was greater than its realisation. It left me pondering the relevance of this in real life, where the idea of owning something was perhaps more exciting than actually obtaining it.

The work moved away from ‘Habitat’ to work devoted to advertising. This is where the mood changed. It moved from the celebration and satirisation of objects in the home to an all out visual offensive, which is only natural when you consider the inescapable medium of advertising. It was overwhelming. Arcade games popped and pinged. Posters plastered to the wall offered the chance to sell your soul, while Chairman Mao was depicted as an enormous figure in a static computer game piece opposite. Here, we start to see the tropes of Pop Art being appropriated by the East: Lenin is the “Real Thing” of Coca Cola and Marlborough’s iconic cigarette packaging has been replaced with “Malevich” and a black square. The work makes you laugh; the mix of dissidence with well-known imagery is slick. Even without the extra layer of mocking the Communist regimes, the Western work that sits amongst this is mocking in its own way, by reflecting back to us the well-worn images of material possessions. We see different humours, but they are united in their critical nature. The critique follows through to religion; the iconography of religious paintings has been blackened out, your focus drawn to a repeated pattern of tins of caviar. Faith, it seems, is garnering less respect than the premise of goods, and lots of them.

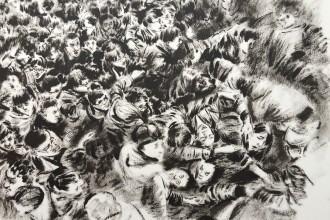

There were many such pastiches of advertising, from beautiful oil paintings with Chinese script, to Dr Martens adverts that have been replaced with very low quality images of soldiers wearing boots in the snow. Consumerism and Communism are brought together: Mickey Mouse holds hands with Lenin and Jesus; Komar and Melamid’s big red flag of Soviet Realism flies boldly in a very traditional oil painting; and the hammer and sickle becomes a hammer and a big silver dollar sign. What I became more and more aware of, as I walked through the rooms, is that, although polar opposites in terms of politics, both the world of advertising and Socialist propaganda are trying to sell you an ideology. There is an ease with which propaganda has been turned into a Pop Art pastiche, and it highlights the similarities of style and ideals of both. They want to be liked. They are both trying to sell something, whether that is a product or a way of life, they want you to be sold by the idealised (and often false) projections of these images.

And still, there were more works. They kept on coming, as though the breadth of Pop Art’s reach is wider than you could possibly think. The work looked at sex, religion, at art made for art’s sake. A contemporary icon is the simple ‘f’ of Facebook that has been transformed into a giant bronze statue. It commands reverence. And maybe, in contemporary society, that is what this little icon has instilled in us. The figures of traditional statues have been carved as wearing Communist style clothing. There were the singed embers of works by Warhol, Rauschenberg and Johns, amongst others. One photograph showed a city landscape constructed mostly with dildos. And yet, this was one area where I lost interest. We are so saturated with images of this nature that it no longer seems shocking, which is perhaps as strong a sentiment for Post-Pop as any—the proliferation of this sort of imagery and how mundane this now appears. Yet, this is a sentiment for Post-Pop as viewed in the UK, by someone that has forever been surrounded by this type of imagery. Taken out of its Western context however, this work would probably not be greeted with such a worn down fatigue.

There was more work than I could possibly comment on and this could almost be the very definition of the impact of Post Pop: vast and all encompassing. Its influence in Russia was seen in the development of Sots Art, where East and West were fused together, and in China, the outcome was Political Pop, where Americanised imagery became galvanised with state approved propaganda. In the work from the East, we see the images of the everyday being transcended into works of art. It is just that these were not images of consumer durables as in the West; they were images of Lenin, of Stalin, of Mao with hoards of happy children. Amongst the direct pastiches, there are glorious hints of dissidence. This is perhaps what Pop Art’s legacy is, to allow the context of well-known images to be subverted. It’s reach spreads across religious, sexual and political imagery and it has been shown to be colourful, humourous and buoyant. I wouldn’t want to know a world without it.

Post Pop: East Meets West is on at the Saatchi Gallery until 3 March 2015.